The weekend of May 10th through the 13th, I had the pleasure to hang out in one of my favorite towns in the country,Palm Springs, at the 12th annual edition of my favorite film festival in the country: The Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival, at the Camelot Theatres on Baristo.

The weekend of May 10th through the 13th, I had the pleasure to hang out in one of my favorite towns in the country,Palm Springs, at the 12th annual edition of my favorite film festival in the country: The Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival, at the Camelot Theatres on Baristo.

As usual this year’s schedule included a variety of hard-to-catch crime films of the mid-20th century.

I caught 1948’s I Love Trouble, with debonair Franchot Tone as a quipping detective caught up in a twisty intrigue, and 1954’s Shield for Murder with Edmund O’Brien as a murderous rogue LA homicide detective.

I also made it to 1960’s Key Witness with a young Dennis Hopper, a fine turn by Frank Silvera as a detective, a terrific jazz score, and some time-capsule views ofEast L.A. special guests this year included vets like Richard Erdman and Pat Crowley.

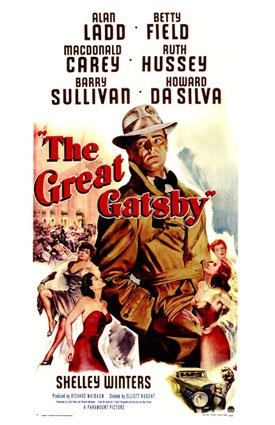

But maybe the most interesting curio on the schedule was Paramount’s obscure 1949 version of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, with Alan Ladd in the title role.

While it’s a rarely shown movie, it’s no lost classic. Despite a fantastic cast—Macdonald Carey as Nick, Betty Field as Daisy, Barry Sullivan as Tom, Ruth Hussey as Jordan, Shelley Winters as Myrtle, and Henry Hull, Elisha Cook Jr., Howard Da Silva and Ed Begley among the supporting players—this version is laughably pedestrian.

Based in part on a stage adaptation by Owen Davis, this Gatsby suffers from banal dialogue and a perplexing absence of the novel’s intrigue and mystery. Good as the cast is, some of them are not well-served by the material: Betty Field, so touching in Of Mice and Men, is particularly excruciating here.

Terrible as the movie is, though, it’s worth seeing if you ever should get the chance. Even in this crude, clumsy retelling, the story, with its adolescent fantasy of romantic gesture blended with its blunt awareness that money trumps romance, has its appeal, and the stripping-away of Fitzgerald’s graceful language throws a striking light on the illusory nature of genre divisions in general.

At first Gatsby struck me as a stretch for inclusion in a noir festival. But then I tried to consider the story aside from its reputation as a highbrow literary classic—infidelity and obsessive love, gangsters and bootleggers, a hit-and-run, a cover-up, a man manipulated into murder, and above all a guy brought low because he’s a sucker for a dame.

How much more “noir-y” did I want it to be?

That Gatsby isn’t seen in terms of the genre is, of course, partly because of Fitzgerald’s elegant style, the opposite of the hard-boiled argot that is associated (incorrectly, for the most part) with noir writing.

But it’s also because of hard-wired literary prejudice—Gatsby is seen (rightly) as top-notch American literature, while novels critically defined as “noir” are frequently seen, by definition, as not quite literature at all.

This attitude may be changing, but it hasn’t changed yet.