By M.V. Moorhead

Lots of people have come forward with stories about their encounters with Muhammed Ali over the years. Now it’s my turn.

The setting for this encounter was a soup kitchen in South Phoenix somewhere—I don’t remember when exactly, but it would have been in the late ‘90s or very early 2000s, when I was at New Times.

It was late on a Friday afternoon, and I think it was around the holidays, as Ali was there to put in some volunteer work and promote the place.

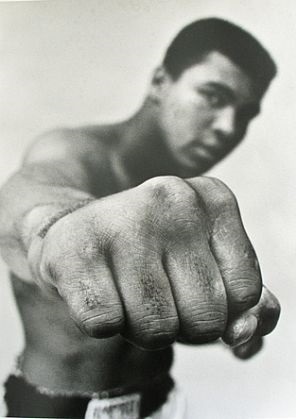

He showed up right on time, got out of the limo, hobbled over to the surprisingly few media people who had shown up, smiled, shook our hands, and mock-punched at a few of us, including me.

Then we followed him into the kitchen, where he was adorned in an apron and toque, and started serving diners. That mock-jab seems to have been a favorite gesture of his — I suspect he wanted to give as many people as possible the right to say that Muhammad Ali once threw a punch at them.

Recently I heard from Wrangler News founder Don Kirkland his remembrance of Betty Bennett, a longtime Valley resident who revelled in her experience of spotting Ali in the lobby of a hotel in Chicago, walking up to him and saying:

“I want you to hit me,” precisely so she could make that boast.

He obliged, tapping her gently on the shoulder with his fist and, as expected, making her the envy of dozens of coworkers as soon as she returned to her office and in the weeks thereafter. Like this lady, lots of people have great stories about Ali, who passed on this month at 74. Some of those recollections are likely better than mine of my fleeting encounter, especially here in the Valley where he became such a public part of the community (some years later I glanced up while walking across a parking lot and saw the words “HAPPY BIRTHDAY CHAMP” sky-written over Paradise Valley).

And my take-away from it isn’t anything special, either—simply that the man had charisma. Even limited by his illness (he didn’t speak at that event, at least not while I was within earshot of him) he had a riveting presence.

Inconsequential as this meeting was to anyone else, however, it meant something to me, because even though I’ve never been a boxing fan, I had been a fan of Ali since childhood.

I vividly remember the early ‘70s, when Ali’s bouts with Joe Frazier were talked about constantly, and the boys I went to school with in mostly white and heavily racist rural Pennsylvania, undoubtedly following what their dads told them, rooted for Frazier, because Ali was seen as uppity.

I always preferred Ali, though, because he was funny. I was terribly disappointed when he lost the “Fight of the Century” in ’71, and my classmates crowed triumphantly.

Lots of people are also far better equipped than I am to discuss Ali as athlete, activist and man. But in the ensuing decades, during which he became one of the most widely admired people in the world—one of the few people toward whom the Irony Generation seemed willing to show some reverence—I have also wondered at times if it’s Ali we have to thank for the culture of “trash-talk” and braggadocio that in recent years has largely replaced modesty and civility as the ideal in sportsmanship, and now other spheres, notably the political.

Ali’s boastful riffs are in the ancient Plautine tradition of the Miles Gloriosus, the Braggart Warrior, but Ali took this persona to a different level—he gave it validity and beauty.

He sometimes took his act too far, by his own admission. He apologized publicly, albeit years later, for some of his taunts at Frazier, for instance.

But his routines, delivered in that mellow yet subtly provoking rasp, were always witty, playful and—most important—undergirded by a palpable love of humankind.

If contemporary athletes, celebrities and political figures imagine that their blustering self-aggrandizement and mindless insulting of rivals are somehow Ali-esque, they’re very much mistaken.

R.I.P., Champ.