Story & photo by M.V. Moorhead

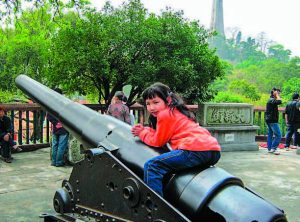

Once upon a time I didn’t know the significance of a red envelope. Nor did I know what moon-cakes or egg-custard tarts were. I knew, courtesy of the paper placemats in Chinese restaurants, that I was born in the Year of the Tiger and my wife in the Year of the Rat, but beyond that I couldn’t have told you much about the Chinese New Year. I couldn’t even have told you with any real confidence when in the year it arrives. That all changed four years ago this month, when my wife and I traveled to China to pick up the daughter we had adopted. We arrived there in very early March, just after the Year of the Rabbit had commenced, and there was still evidence of the big-time party that had just occurred. Chinese New Year is celebrated with some events and festivities here in the U.S. On Saturday, Feb. 21, for instance, you could participate in the Chinese New Year 5k Run and “Wok” at Papago Park. But over there we could see the true scale of the celebration, even having come just after it wrapped up. It wasn’t until we got home that we began to learn the fascinating specifics about this most momentous of Chinese holidays, which runs for half a month starting with the Lunar New Year—that is, the second New Moon after the Winter Solstice. This year’s fest, ringing in the Year of the Ram, began on Friday, Feb. 19, and is now in progress. We soon learned, for instance, that it is traditional to give kids money in red envelopes—preferably in even amounts, for added luck. We learned to relish flaky tarts filled with sweet yellow egg-custard, as well as dense mooncakes with bean filling, inscribed on top with lucky Chinese characters—actually a traditional autumn festival treat but no less delicious at the New Year. We learned the supposed traits of the animals symbolizing the 12-year Chinese zodiacal cycle. The irony, of course, is that while I have gotten a deeper understanding and appreciation of this cultural tradition, my daughter hardly thinks of it at all. She looks forward, like so many American kids, to Halloween and Christmas, and she spent the early part of this month looking forward not to fireworks and lion parades but to Valentines. When we hand her a red envelope, she’s happy enough to get the few bucks inside, but if we didn’t, I doubt she’d notice the omission. In the few years she’s been over here, she’s worked hard to become a “regular” American kid, and to a great extent she’s succeeded—to more of an extent, in some ways, than I’d prefer. But that food still gets her. Set sticky rice or pork buns or virtually any kind of dumpling in front of her, and there’s no mistaking that, much as I hate to employ the cliché, you can take the girl out of China, but you can’t take China out of the girl.

Once upon a time I didn’t know the significance of a red envelope. Nor did I know what moon-cakes or egg-custard tarts were. I knew, courtesy of the paper placemats in Chinese restaurants, that I was born in the Year of the Tiger and my wife in the Year of the Rat, but beyond that I couldn’t have told you much about the Chinese New Year. I couldn’t even have told you with any real confidence when in the year it arrives. That all changed four years ago this month, when my wife and I traveled to China to pick up the daughter we had adopted. We arrived there in very early March, just after the Year of the Rabbit had commenced, and there was still evidence of the big-time party that had just occurred. Chinese New Year is celebrated with some events and festivities here in the U.S. On Saturday, Feb. 21, for instance, you could participate in the Chinese New Year 5k Run and “Wok” at Papago Park. But over there we could see the true scale of the celebration, even having come just after it wrapped up. It wasn’t until we got home that we began to learn the fascinating specifics about this most momentous of Chinese holidays, which runs for half a month starting with the Lunar New Year—that is, the second New Moon after the Winter Solstice. This year’s fest, ringing in the Year of the Ram, began on Friday, Feb. 19, and is now in progress. We soon learned, for instance, that it is traditional to give kids money in red envelopes—preferably in even amounts, for added luck. We learned to relish flaky tarts filled with sweet yellow egg-custard, as well as dense mooncakes with bean filling, inscribed on top with lucky Chinese characters—actually a traditional autumn festival treat but no less delicious at the New Year. We learned the supposed traits of the animals symbolizing the 12-year Chinese zodiacal cycle. The irony, of course, is that while I have gotten a deeper understanding and appreciation of this cultural tradition, my daughter hardly thinks of it at all. She looks forward, like so many American kids, to Halloween and Christmas, and she spent the early part of this month looking forward not to fireworks and lion parades but to Valentines. When we hand her a red envelope, she’s happy enough to get the few bucks inside, but if we didn’t, I doubt she’d notice the omission. In the few years she’s been over here, she’s worked hard to become a “regular” American kid, and to a great extent she’s succeeded—to more of an extent, in some ways, than I’d prefer. But that food still gets her. Set sticky rice or pork buns or virtually any kind of dumpling in front of her, and there’s no mistaking that, much as I hate to employ the cliché, you can take the girl out of China, but you can’t take China out of the girl.